Philosophy of Teaching 2007

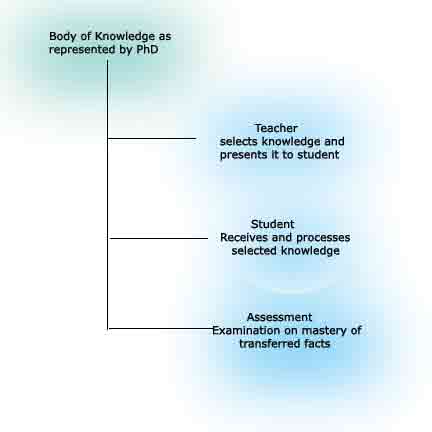

Once upon a time, a long time ago, I believed that, as a professor, scholar, and teacher I possessed an enormous amount of knowledge which it was my duty to transfer in large quantities to my students. In this model of teaching, I was the conduit that enabled students to track along the path that led from knowledge to professor to selected knowledge to student. In this model, assessment was always based on the amount of knowledge absorbed by the student and processed according to the way I, as teacher, wanted it processed. The closer the student came to reproducing me, my selected material, and my analytical and critical process, the closer the student came to the magical A grade and a chance to attend graduate school.

This teaching process gave a model that looked somewhat like this:

Figure 1: the top down model

While this model worked well for me for many years, it is one with which

I gradually grew more and more uncomfortable. As I grew older, I grew more

distant from graduate school and my theories of total mastery of the subject.

More important, I also began to realize that what was important to me within

my subject area was no longer of importance to my students. The growing age

gap between teacher and taught also meant that the transfer of knowledge had

to take place on different planes and different levels.

In order to help bridge this gap, at the beginning of the school year, I began

to introduce myself to each class I taught. I presented my qualifications,

I explained what I could teach, and why; I even explained some of the things

I could not and why not. Then I began asking the students if there were any

questions. One question I always got was “How long have you been teaching?”

and this was often followed by the question “Aren’t you bored

with teaching the same subject all those years?” I always answered,

and still answer, “No!” to the second question. But I have thought

often and long on the reasons for which I am not bored. One of them is quite

clear: I am not bored after all these years simply because I do not teach

a subject and a body of knowledge. Rather, I teach people; and every year

the people are different, their backgrounds are different, and their interests

are different. Therefore, I am never bored because the people I teach are

always fresh and new and never the same. This realization has led me to develop

a very different philosophy of teaching. If I do not teach a subject, but

the people who study the same subject as I am offering, what has changed?

How do I make a class student orientated versus content orientated? How has

my actual methodology and philosophy changed?

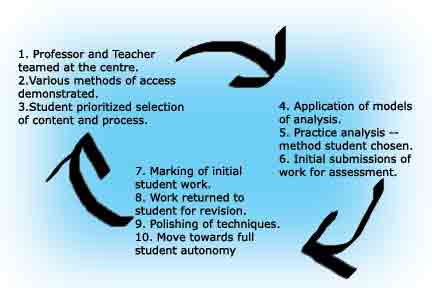

In my new student-centered model, I realize that the content I actually teach varies with each student. What I am teaching is less a body of content and much more a way to access content. In addition, I have come to believe that students must be offered ways in which to organize, process, and understand that content. Access and understanding, then, become more important and I attempt to assist each student to advance, not along my path, but along their own path, to knowledge. Self-development in the student’s chosen field, which is not always my chosen field, becomes paramount. This demands a new model in which the student and the student’s needs are all important. In this new model the professor links directly to the student, rather than to the content, and provides a series of ways in which to access and understand content which the student actually chooses.

In other words, the student is shown how to access the body of knowledge, which is left open for the student’s selection. In this model, a series of examples are selected by the teacher from the body of knowledge. These examples are presented to the student to show what the student might do and how he or she might proceed. Each example is accompanied by an information sheet which lists a variety of procedures that may be used to examine the example. Each student is encouraged to modify the information sheet according to (a) his or her own knowledge and interests and (b) according to the example under study. Clearly, this later model totally negates the earlier model of “teacher knows best” by encouraging the student to first develop a personal method and then to move out from that method into the enormous, and constantly expanding, world of content.

Assessment then takes place at several levels: (1) a traditional test, taken earlier, to ensure that there is an initial mastery of sample ways of access to the model; (2) a series of information sheets produced by the student; and (3) a major term paper which is selected by the student, shaped by the student, and follows the model of the information sheet as re-constructed by the student.

This allows us to establish the following perpetual motion model for a philosophy of teaching:

Figure 2: The perpetual motion model

In this model, the role of the teacher is to develop strategies by means of which the student can (a) access the course content or knowledge source that is to be studied; (b) develop a process for the examination of the knowledge content; (c) develop a process by means of which the student can record information and analyze it critically; and (d) polish the writing skills which are needed to write up the theme or question which the student has chosen to study.

Add the knowledge explosion which faces us all to the very different individual skills which our students possess and the various different tasks with which they will be faced across their working and studying lives, this method of teaching appears to me to hold much great promise for the development of the student.